Museo archives Giovanni Boldini Macchiaioli | The Macchiaiolis

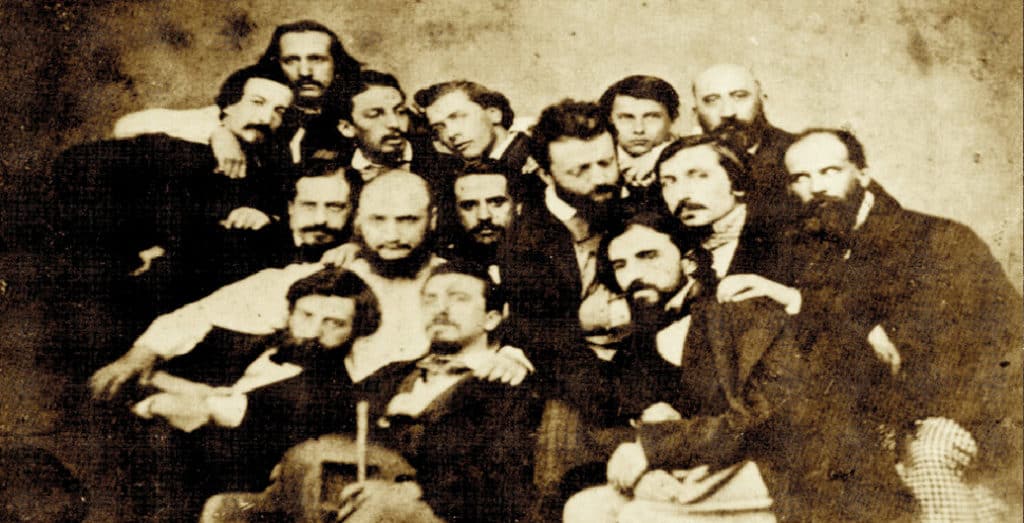

The Macchiaiolis’ artistic movement was among the most important international movements of its kind in the 800s. It was born in Florence through the desire of some artists who, as from 1856, met at the Michelangelo Café, near the local Academy, to freely exchange and discuss ideas and philosophic innovations regarding painting.

The artists who took part in the movement during the crucial years between 1856 and 1868 were : Giuseppe Abbati (1836 – 1868), Saverio Altamura (1822 – 1897), Cristiano Banti (1824 – 1904), Giovanni Boldini (1842 – 1931), Odoardo Borrani (1832 – 1905), Luigi Bechi (1830 – 1919), Vincenzo Cabianca (1827 – 1902), Adriano Cecioni (1836 – 1886), Vito D’Ancona (1825 – 1884), Giovanni Fattori (1825 – 1908), Silvestro Lega (1826 – 1895), Antonio Puccinelli (1822 – 1897), Raffaello Sernesi (1838 – 1866), Telemaco Signorini (1835 – 1901), Serafino De Tivoli (1826 – 1892).

The young artists – some of whom were also participating in the wars of Independence – became aware of the need to confront each other with regards to the artistic changes in Europe, in particular what was happening to French artistry, where a completely new language was undergoing an extremely innovative, synthetic and expressive codification.

Many other Italian artists committed themselves to the renewal of the aesthetic language of the 800s, but the Macchiaiolis’ movement was the only one considered to be a real school, both with regards to the common intentions of the group members and also for the quality of the research and the experimentations which were carried out. Among them were some real theorists like the artists Adriano Cecioni, Telemaco Signorini as well as the critic and patron, Diego Martelli.

The “Macchia” (“The Stain” – Sketch) counteracted the ethical and pictorial dictates of the Florentine Academy which imposed on its students subjects derived from literature of history and even carried out with techniques tending towards photographic perfection, always identical to themselves.

The young innovators, on the other hand, suggested life as an expressive, avant-garde lexicon, going outdoors to paint, only selecting subjects that they could really see with their own eyes : the “real life”. The result was a gush of numerous essential styles, characterized by strong shades among light and shadow.

The term “macchiaioli” was however coined some years later – it was disparagingly accepted for the first time, in La Gazzetta del Popolo in 1862. The artists were accused of reducing paintings to mere sketches, to a group of stains, thus evidencing the net refusal of academic drawing in favour of the “macchia” (“stain”) and of the effects of colour tones.

Subsequently, the name was adopted by the group’s members themselves. These artists, broke away from Classicism and Romanticism, thus renewing the Italian pictorial culture and are therefore considered as the initiators of modern Italian painting.

Their theories claimed that the “del vero” (“real life”) image presents itself like a contrast of stains of colours and shades. Such effects were even easier to acquire by observing the landscapes through the reflection of a dark mirror, darkened by smoke (a technique called “ton gris”), thereby able to completely filter the contrasts of shades, thus representing and enhancing the contrasts of the shades within the painting itself.

The technique employed by these artists consisted in bringing real life impressions into the painting itself through light and dark stains. Apart from landscapes, one of the themes preferred by the Macchiaiolis, were also scenes of domestic and daily life. Many works, especially between the end of the 1850s and the beginning of the 1860s, represented soldiers and battles. Themes which then became customary for the school leader, Giovanni Fattori, during his entire life. In fact, most of these artists participated in independence wars, as volunteers, and fought for a United Italy.

Members of the movement, and their works, were subsequently more sensitive and influenced by the historical, cultural and local events of their times and also, if not declared directly, they considered art not only as an instrument of aesthetic expressiveness but also as a means of communication for ideological affirmation and testimony.

During the process of social modernization which accompanied the community of the 800s, the “Macchia”, having freed itself from noble and royal obligations, assumed the honour of representing reality just as it presented itself in the eyes of the artist, called upon by a common civic sense of the Risorgimento and by a love of one’s country, to photograph the lives of the more disabled, frequently subjected to heavy work in the fields or those humble ones in the cities. In a kind of naturalistic celebration and civil alliance among man, nature and civil atmosphere, especially in the second half of the century, the artist caught the sense of suffering, and, at the same time, dignity of the centuries-old country town civilization which made up the social foundations of the small, national states, which were united under the Savoy banner.

The emarginated conditions and discomfort of the peasant world, sometimes offering crude visions, sometimes tormenting, were represented by the greatest artists of the century and in Italy, among all, by the Macchiaioli’s group. They were the years of revolt and of modern social conquests, and then of urban remodernization of Florence, Capital of Italy: the peasants moved from the fields into the cities, populating the surroundings and the factories, triggering a process of amalgamation with the Florentine middle class.

The renewed interest in Italian paintings of the 800s, in the last thirty years, has given us a way to enrich the catalogue of critical, historical studies by examining the aspects of life, and above all, the artistic body of some of the major artists of that period.

About 100 highly-significant works of Italian school leaders, active in Florence, some fighting men and Risorgimento heroes, make up the museum collection, representing in every aspect, the avant-garde forms of the 800s, whose research and innovative contents are above all about the expressive power of light.